Key Fossils

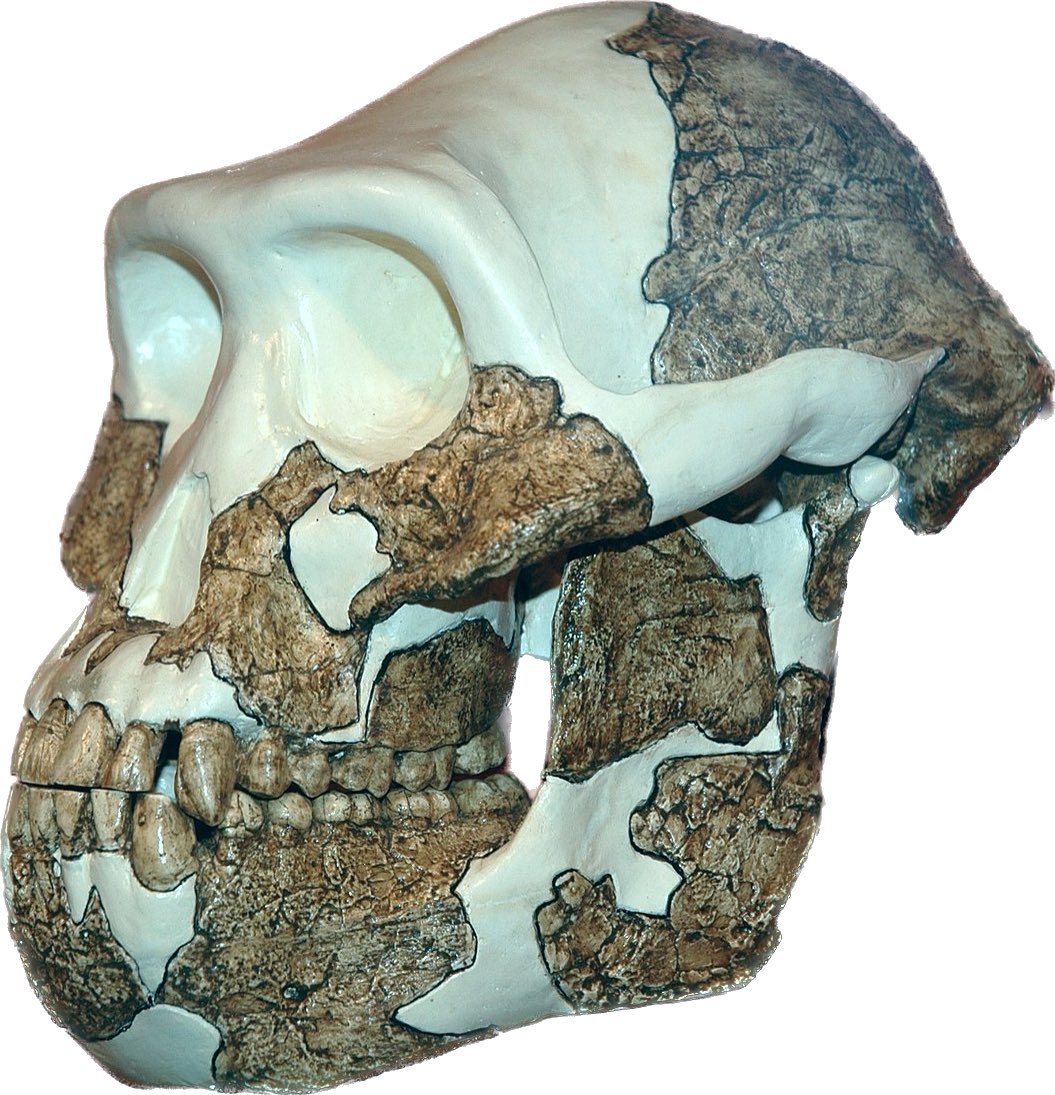

Sahelanthropus tchadensis

Nearly complete cranium, possibly the earliest known hominin. Shows reduced canines, more forward-positioned foramen magnum (suggesting bipedalism), and mosaic of ape/human traits. Brain size ~350cc.

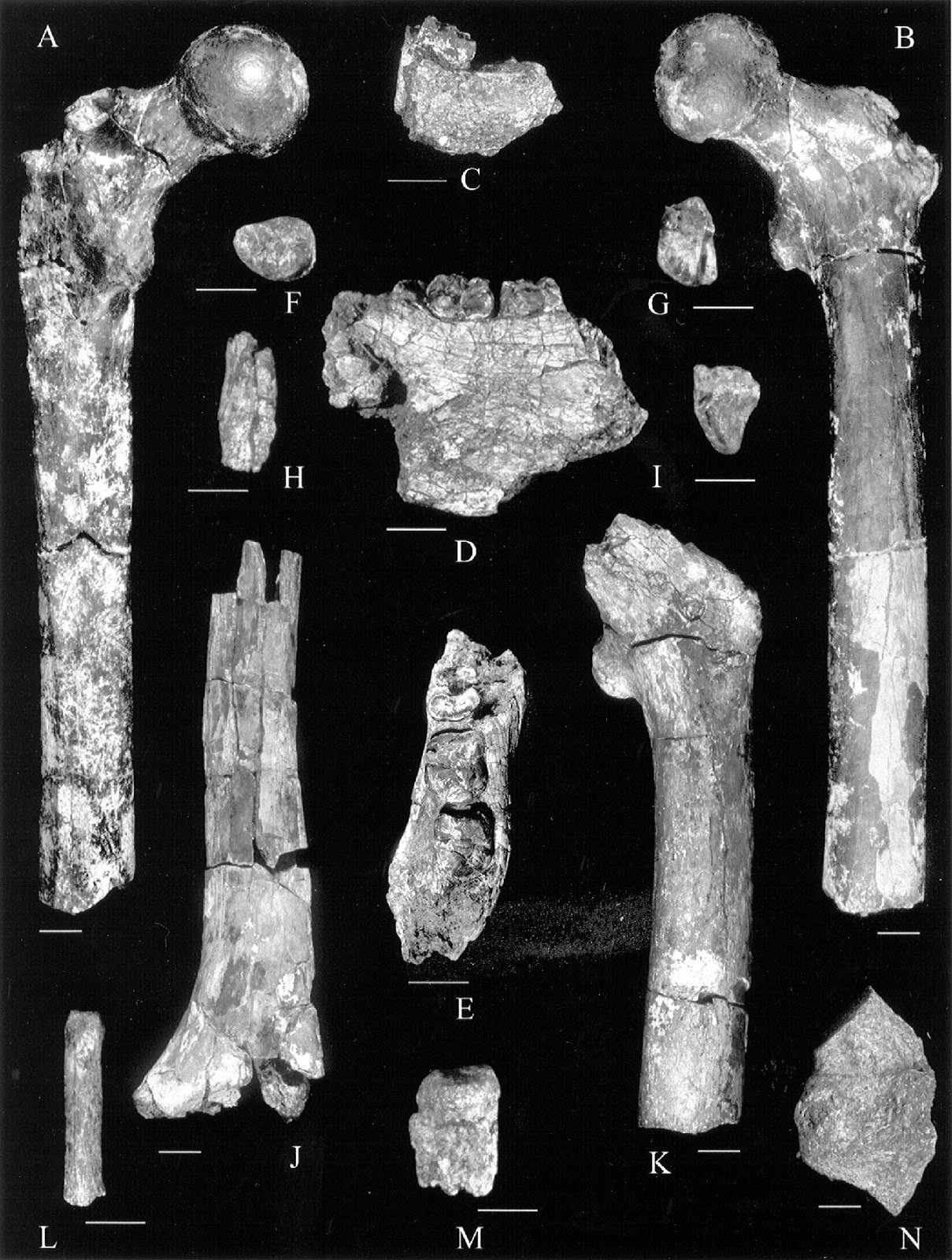

Orrorin tugenensis

Known from teeth and postcranial fragments. Femur morphology suggests bipedalism. Found in Tugen Hills, Kenya.

Ardipithecus ramidus

Teeth and partial skeleton fragments. Toe bone suggests bipedal adaptations. Brain size estimated ~350cc.

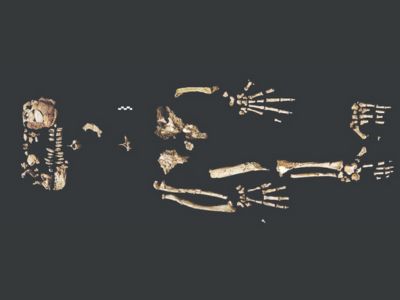

Ardipithecus ramidus

45% complete skeleton with unique mix of ape (divergent toe) and human (pelvis adapted for upright walking) traits. Brain size ~350cc.

Australopithecus anamensis

Likely ancestor to A. afarensis. Tibia shows weight-bearing adaptations for bipedalism. Brain size ~370cc.

Australopithecus afarensis

Fully bipedal (Laetoli footprints) with ape-like proportions & tree-climbing adaptations. Brain size 380-430cc.

Kenyanthropus platyops

Flat-faced hominin. Possible separate lineage from Australopithecus. Brain size ~400cc.

Australopithecus africanus

First australopithecine discovered (1924). More human-like face than A. afarensis. Brain size 420-500cc.

Paranthropus aethiopicus

Robust skull with large sagittal crest for chewing muscles. "Black Skull" KNM-WT 17000. Brain size ~410cc.

Australopithecus garhi

Associated with earliest known stone tools (Oldowan). Possible Homo ancestor. Brain size ~450cc.

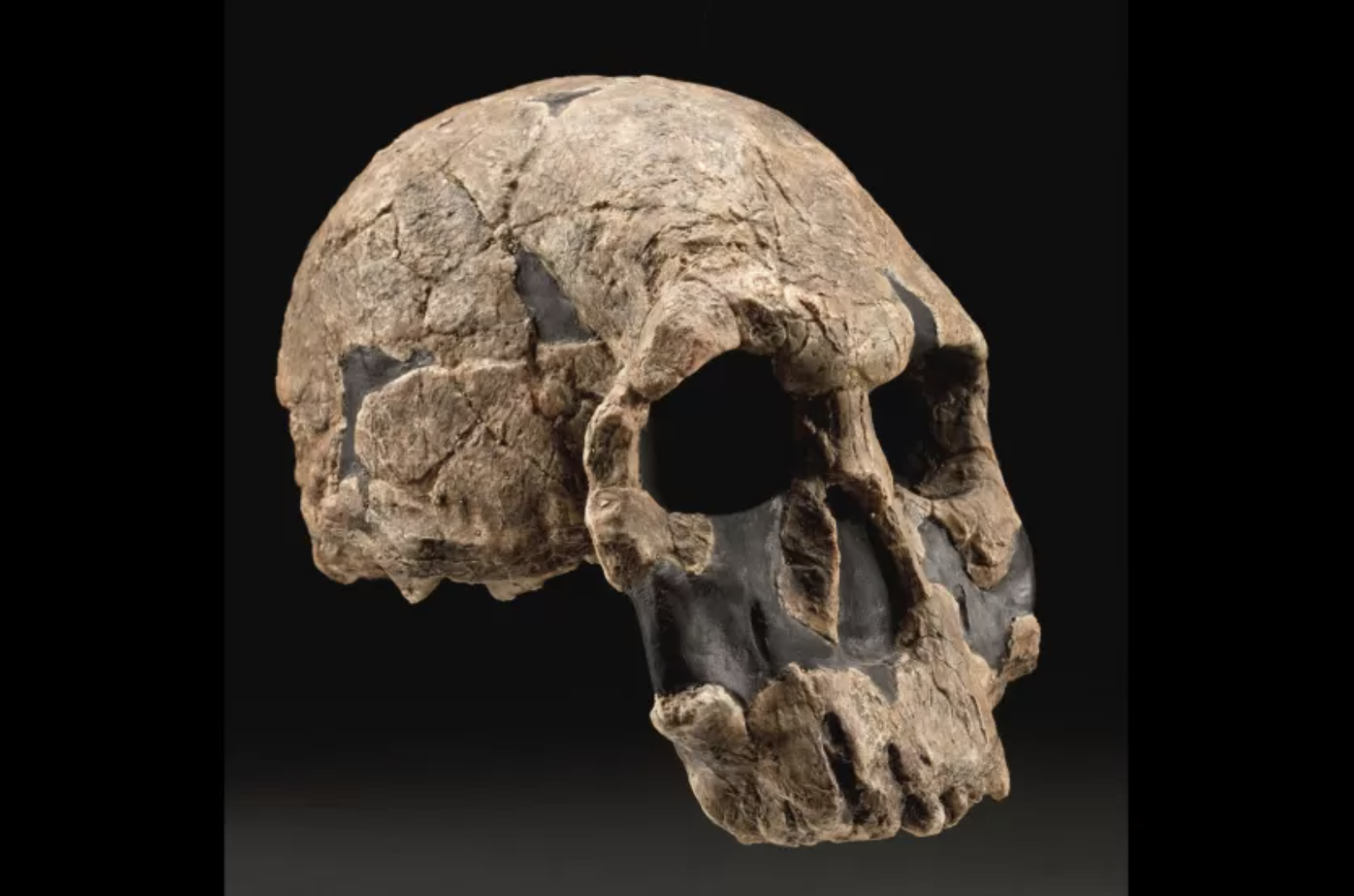

Homo habilis

First species in our genus. Associated with Oldowan stone tools. Brain size 500-650cc.

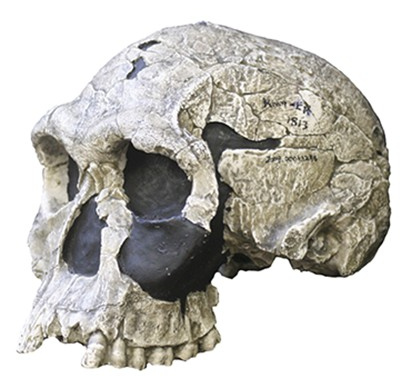

Homo rudolfensis

Well-preserved cranium with larger brain capacity (~750cc) but primitive face. Discovered at Koobi Fora.

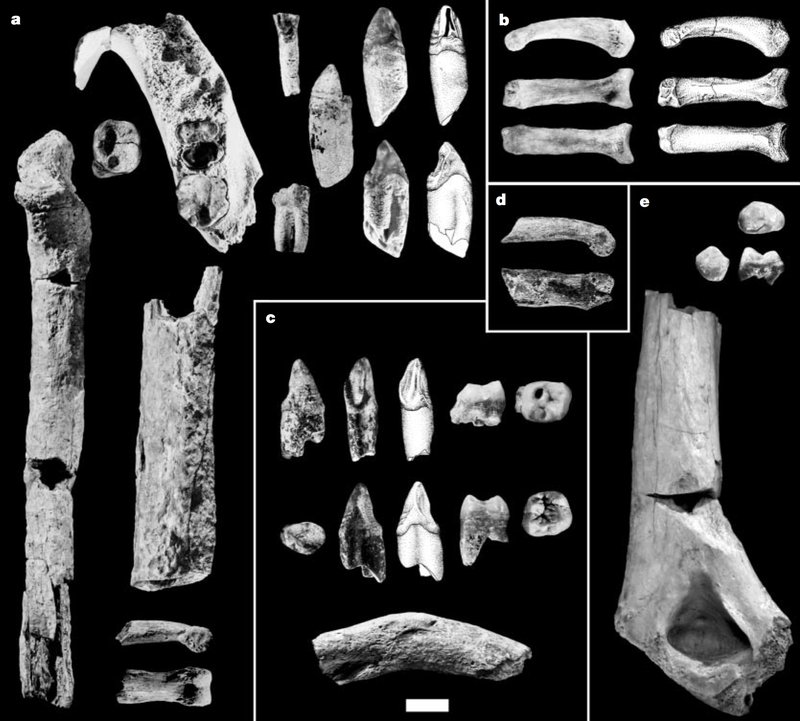

Paranthropus boisei

Massive molars and jaw muscles for tough plant foods. Brain size 500-550cc.

Paranthropus robustus

South African robust australopithecine, specialized for heavy chewing. Brain size ~530cc.

Australopithecus sediba

Mosaic of australopith and Homo features. Possible transitional species. Brain size 420-450cc.

Homo erectus

Earliest definitive evidence of hominins outside Africa. Shows remarkable variation within a single population. Brain size ~550-780cc.

Homo ergaster

Nearly complete skeleton of a juvenile. Body plan very similar to modern humans but with smaller brain (~880cc projected adult). Considered African variant of H. erectus.

Homo antecessor

Earliest known European hominin (Gran Dolina fossils). Brain size ~1000cc.

Homo heidelbergensis

Potential ancestor to both Neanderthals and modern humans. Brain size 1100-1400cc.

Homo naledi

Over 1,500 specimens from Rising Star cave. Small brain (465-560cc) but human-like hands/wrists. Suggests deliberate body disposal.

Homo sapiens (Jebel Irhoud)

Earliest known H. sapiens fossils. Modern-looking face and teeth but more primitive elongated braincase. Pushes back origin of our species.

Denisovans

Known primarily from DNA (finger bone, teeth, mandible). Revealed previously unknown hominin species that interbred with modern humans.

Homo neanderthalensis

Neanderthal skeleton showing healed injuries, suggesting care from others. Part of multiple burials in Shanidar Cave, some with possible flower offerings. Brain size 1200-1750cc.

Homo luzonensis

Recently discovered species from Luzon. Mix of primitive (curved phalanges) and derived features.

Homo neanderthalensis

Well-preserved "Old Man" skeleton. Distinctive robust features, large brain case, evidence of deliberate burial.

Homo floresiensis

Adult female only ~3.5 ft tall. Brain size 380cc. Island-dwelling species that made sophisticated tools despite small brain.

Homo sapiens

One of the first early modern human fossils discovered (1868). Fully modern anatomy. Associated with advanced Upper Paleolithic tools.

Transitional Features

Bipedalism

Adaptations for upright walking appear earliest, with evidence in Sahelanthropus (7 mya, foramen magnum position), Orrorin (6 mya, femoral neck), and Ardipithecus (4.4 mya, pelvis). The Laetoli footprints (3.6 mya, Tanzania) provide direct evidence of bipedal walking in Australopithecus. Bipedalism evolved before significant brain expansion, with early hominins having chimp-sized brains but upright posture.

Brain Size

Gradual increase in cranial capacity: Early hominins (350-400cc), Australopithecines (400-550cc), Homo habilis (500-650cc), Homo rudolfensis (700-750cc), Homo ergaster/erectus (700-1100cc), Homo heidelbergensis (1100-1400cc), Neanderthals (1200-1750cc), Homo sapiens (1000-1700cc). Brain size tripled over 7 million years of evolution.

Dentition

Reduction in tooth size and jaw robusticity over time. Canine reduction and molar shape changes are earliest hominin traits. Australopithecus still had relatively large molars; gradual reduction through Homo. Dental formula remained consistent (2:1:2:3) while tooth morphology changed. Paranthropus species show specialized megadont dentition for tough plant foods.

Cranial Features

Progressive changes include: reduced prognathism (facial projection), decreased postorbital constriction, reduced supraorbital torus (brow ridge), increased cranial globularity, development of chin (unique to H. sapiens), and reduced cranial thickness. Early Homo species show mosaic of primitive and derived traits.

Postcranial Anatomy

Changes include: shortened arms relative to legs, curved lumbar spine, bowl-shaped pelvis, angled femur, arched feet, and non-opposable big toe. Homo ergaster/erectus (1.8 mya) shows first fully modern body proportions. Neanderthals developed cold-adapted features: barrel chest, shortened distal limbs, robust build.

Changes include: shortened arms relative to legs, curved lumbar spine, bowl-shaped pelvis, angled femur, arched feet, and non-opposable big toe. Homo ergaster/erectus (1.8 mya) shows first fully modern body proportions. Neanderthals developed cold-adapted features: barrel chest, shortened distal limbs, robust build.

How do we know the age of these fossils?

Multiple independent dating methods confirm the ancient age of human fossils:

- Radiometric dating: Potassium-Argon and Argon-Argon dating of volcanic layers surrounding fossils (reliable from 500,000 to 4.5 billion years ago). Used for dating Olduvai Gorge fossils (Tanzania) and Koobi Fora (Kenya).

- Uranium series dating: Used for cave deposits and fossil teeth (up to 500,000 years old). Applied to Atapuerca fossils (Spain) and Rising Star Cave (South Africa).

- Electron Spin Resonance (ESR): Used on tooth enamel (range: 1,000 to 2 million years). Applied to Sima de los Huesos fossils (Spain) and Border Cave (South Africa).

- Radiocarbon dating: For younger fossils (up to 50,000 years old). Used for dating late Neanderthal remains and early modern humans in Europe.

- Paleomagnetism: Magnetic reversals in sediment provide timeline markers. The Olduvai subchron (1.95-1.78 mya) helps date early Homo fossils.

- Biochronology: Dating based on associated animal fossils with known time ranges. Used when direct dating methods aren't applicable.

- Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL): Measures when sediment was last exposed to light (up to 350,000 years). Applied to Jebel Irhoud (Morocco) and Denisova Cave (Russia).

Is there other preserved evidence?

Archaeological evidence shows gradual development of human behaviors:

- Stone tools: Oldowan (2.6 mya, simple flakes), Acheulean (1.76 mya, hand axes), Mousterian (300,000 ya, prepared core), Upper Paleolithic (50,000 ya, blade tools).

- Fire use: Earliest evidence from Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa (1 mya), controlled use by Homo erectus. Hearths common in Neanderthal sites by 400,000 ya.

- Symbolic behavior: Shell beads (Blombos Cave, 75,000 ya), ochre use (Pinnacle Point, 164,000 ya), cave art (Sulawesi, 45,500 ya; Chauvet, 37,000 ya).

- Burials: Earliest intentional burials by Neanderthals (Shanidar Cave, 70,000 ya) and H. sapiens (Qafzeh, 100,000 ya).

- Complex technology: Compound tools (hafted spears, 400,000 ya), bone tools (Blombos Cave, 80,000 ya), bow and arrow (Sibudu Cave, 64,000 ya).

Conclusion

The human fossil record provides strong evidence for human evolution over millions of years. From hundreds of specimens found across four continents, we see a clear progression from ape-like ancestors to modern humans with transitional forms along the way.

Rather than appearing suddenly, modern human traits emerged gradually over time: bipedalism first (7-4 million years ago), followed by tool use (2.6 million years ago), brain expansion (starting ~2 million years ago), and finally modern anatomy and behavior (300,000-100,000 years ago).

This evidence directly contradicts the idea that humans appeared in their current form without evolutionary precursors and confirms our shared ancestry with other primates.